Grace Pagnucco

Charles Kingsley’s The Water-Babies: A Fairy Tale for a Land-Baby brings to life wonderful underwater scenery with unique characters for the reader to explore and immerse themselves in. Many versions of the novel have included illustrations by various artists to go along with the story to visually display the world Kingsley created. As Richard Beards explains in his introduction to the novel though, “the story’s wealth of visual possibilities … challenged its illustrators’ imaginative powers”, especially since Kingsley never provides a description of the main creatures, the water-babies, themselves (xiii). Because of this expansive detailed world and lack of direction from the literature, the illustrations from these artists are all vastly different but equally beautiful as they represent The Water-Babies in their own way. One of these artists is Sir Joseph Noël Paton, a painter and illustrator from Scotland, who had the honor of creating the illustrations for the novel’s first volume publication in 1863. Paton combined his experiences as a painter in both the pre-Raphaelite and fairy art movements of the Victorian era with classical religious imagery and natural science illustration to create the two plate drawings for the novel. As a result, Paton’s versions of scenes from the novel, with the influence of his various experiences and the changing social and cultural ideals of the time, both display and contradict the themes Kingsley included in The Water-Babies.

The Pre-Raphaelite Movement

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, a small group of young artists that was the precursor to the movement of the same name, was first set up in 1848 (Lessens). Students of the Royal Academy of Arts at this time were expected to specifically put emphasis on “hierarchy, on drawing, on indoor painting, on a smooth and invisible brush stroke, and last but not least on the reference to Antiquity and to the Renaissance” in their works (Lessens). These strict standards and expectations didn’t agree with some students, who wanted more freedom to explore beyond the “so-called perfect” compositions, poses, and overall artistry of Antiquity and Renaissance painters like Raphael, and the pre-Raphaelites were born (Lessens). Instead of these classical characteristics of art, the pre-Raphaelites strived toward authenticity, mannerism, and naturalism (Lessens). In contrast to the traditional hierarchy pyramid compositions, with the main figure at the top and in the most light and focus, the pre-Raphaelites displayed their subjects in more natural and equal poses and arrangements (Lessens). In a similar way, the pre-Raphaelites also incorporated emphasis on light and natural beauty in their works as opposed to the traditional shaded corners and dark undetailed backgrounds (Lessens).

The pre-Raphaelite movement, against this push for classical technique, also strove to concentrate intensely “on the faithful representation of natural forms and on observation from nature” (Bown 110). Artists that were a part of the movement worked to accurately display natural scenes of people, animals, and environments while also emphasizing their beauty. This included natural poses, proportions, composition, scenery, lighting, and color. Some pre-Raphaelite works can even be described as more “erotic” due to their female subjects’ long flowing hair and bosomy physique, reminiscent of the movement’s goal of focusing on natural beauty and realism. Because of this focus on naturalism, pre-Raphaelite works “baffle[d] the spectator with their minute delineation of details which the viewer must work to make sense of” and were often compared to natural history and field guide illustration (Bown 44, 110). Paton himself was attracted to this “select nothing, reject nothing” doctrine, one that refused to represent subjective, incomprehensive, and selective subjects, and incorporated it into his work (Story 102).

The Victorian age involved a similar evolution of religious ideals as well, as an emphasis on nature, growth, and realistic life in relation to faith begins to take root. For Kingsley specifically, hard work, cooperation, and well-mannered behavior are all qualities of a good Christian young man. As Klaver explains in his comprehensive biography of Kingsley, “a standard of manliness which is based on hard work and a team spirit, is to Kingsley the true expression of ‘Young England’” (445). Klaver also brings up the fact that “The early nineteenth-century saw nature in the light of natural theology as the vox dei on rebus revelata [“the Word of God revealed in facts”], and as such it was proper for a clergyman (and his family) to investigate nature in a scientific sense” (17). In Kingsley’s eyes, and the eyes of others at the time, spirituality included a physical connection with nature and work, to see “the Word of God revealed in facts”, as well as in scripture. These ideas of connecting to God by connecting to nature are very different from common religious imagery that would have been seen in the Renaissance era that helped create the standards of fine art that were upheld at the time. The pre-Raphaelites incorporated many of these ideas of natural beauty and a realistic work-life into their own religious work, as the movement’s ideals mirror them.

In classical works, like the religious art of the Renaissance for example, the standard inexpressive contrapposto pose, or standing straight with one’s weight focused on one leg, was common, as well as other “tense” or even “jerky” poses (Lavin 91, 92). Scenes with supernatural settings like heaven were also common, and members holy family specifically were often shown above other figures in the works. Symbols like golden halos above holy figures and crosses made from a variety of materials were widely used in classical works as well, as were images of infants, cherubs, and the depiction of the “Madonna and Child”, or Mary with baby Jesus. Due to the “Florentine interest in the graces of childhood,” infants were often associated with innocence in the time of the Renaissance (Lavin 85). “Madonna and Child” images encapsulated this sentiment by displaying Jesus, a symbol of purity and holiness himself, as an infant with his virgin mother. The depiction of cherubs, or winged infants, in religious works was also prevalent for the same reason. For example, in Raphael’s painting Sistine Madonna, we see Mary and infant Jesus together as the main focus of the painting, with a saint on either side of them (fig. 1). They stand upon the supernatural setting of heavenly clouds as cherubs peek over the bottom (fig. 1). Mary stands in the contrapposto pose and is the center of attention, with the most light and focus on her and infant Jesus (fig. 1). The obscured and unfocused background also contains what seems like hundreds of cherubs watching the scene before them (fig. 1). The cherubs specifically in the foreground of this painting can be seen as “’innocent and soulful’”, even representative of the “’worshipper’s longing and devotion’” as symbols of young faith (Emison 242).

In pre-Raphaelite religious works these classical symbols of halos, infants, and the holy family are also prevalent, but they are displayed in very different, more realistic ways. The pre-Raphaelites created scenes that displayed holy figures as more “down to Earth”, with natural poses and scenes of every-day life, like in J. E. Millais’ painting Christ in the House of His Parents (fig. 2). In Christ in the House of his Parents, the holy family is not glorified or presented as “above” the others in the scene in any way (fig. 2). In fact, we see a child Jesus, Mary, Joseph, and a few others surrounded by Joseph’s carpentry tools, presenting them in a more realistic way than standing in clouds surrounded by cherubs like in Sistine Madonna (fig. 1, 2). Young Jesus and Mary are painted lower than anyone else in the painting as well, contrary to classical pyramid composition (fig. 2). There are no halos, no significant visual ways to distinct the holy family from the others in scene besides child Jesus’s bleeding hand (fig. 2).

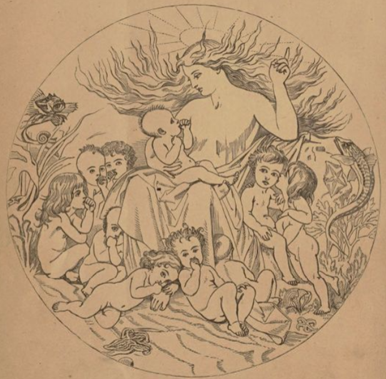

Paton’s illustrations for The Water-Babies seem to incorporate characteristics from both the more traditional religious style and the pre-Raphaelite style. In the novel, the beautiful and kind Mrs. Doasyouwouldbedoneby visits the water-babies of St. Brendan’s fairy isle every Sunday to sing songs to them, tell them stories, cuddle them, and be a loving mother to them (116; ch. 5). Paton’s first plate illustration displays a representation of Mrs. Doasyouwouldbedoneby telling the gathered water-babies a story (fig. 3). In the novel, Mrs. Doasyouwouldbedoneby is described as having the “sweetest, kindest, tenderest, funniest, merriest face” that anyone has ever seen, despite one not being able to distinguish specific features when looking at her (116; ch. 5). She is depicted in the image with a halo above her head, a classic symbol of divinity and power, while her long flowing hair and bosomy physique resemble the pre-Raphaelite “erotic” style that Paton often painted in (fig. 3). The image of Mrs. Doasyouwouldbedoneby with a water-baby on her lap looking up lovingly at her is also reminiscent of the “Madonna and Child” works common in the Renaissance era, like in Raphael’s Sistine Madonna (fig. 1). The water-babies, depicted as infants, are another classic image associated with purity and grace. At the same time, they are posed naturally in a life-like pre-Raphaelite style, in contrast to stiff Renaissance poses (fig. 2). Each figure in the image is unique and expressive, not rigid and overexaggerated.

In a similar way to how the image resembles classic and pre-Raphaelite religious art, the illustration also relates to and contradicts The Water-Babies’ religious themes. This illustration depicts the scene in the novel where Mrs. Doasyouwouldbedoneby tells the attentive water-babies the story of Jesus’ birth, the story of Christmas (118; ch. 5). The pose of Mrs. Doasyouwouldbedoneby with Tom in her arms mirrors the “Madonna and Child” works of the classical era, especially since the story she is telling is a Biblical one (fig. 3). The image of the water-babies looking up to a visually “holy” figure in Mrs. Doasyouwouldbedoneby also seems to visually display the novel’s theme of learning, understanding, and applying one’s morals, or right from wrong (fig. 3). In the novel’s introduction, Richard Beards describes The Water-Babies as being littered with “pointed asides about behavior, how a young gentleman must act, and so on” (xiv). This follows Kingsley’s held ideals of a more “manly” Christianity as the children are being taught good behavior by a kind authoritative figure, especially since the accompanying illustration presents Mrs. Doasyouwouldbedoneby with the symbol of a halo (fig. 2). Being able to visually see the scene furthers the sense of good moral behavior the novel presents. At the same time, the depiction of Mrs. Doasyouwouldbedoneby in the pre-Raphaelite “erotic” style seems to contradict her presentation in the novel as a role model motherly figure. She is described as having “whole rows and regiments” of children of her own, and treats the water-babies as if they were hers by cuddling them, playing with them, and entertaining them with stories and songs (116-117; ch. 5). When she hears that Tom has never had a mother, Mrs. Doasyouwouldbedoneby picks him up and focuses all of her attention on him while the other babies clamor for her affection at her feet (117; ch. 5). While the novel presents Mrs. Doasyouwouldbedoneby as a kind of domestic loving mother figure, Paton’s illustration presents her as stunning young woman. The more erotic depiction of Mrs. Doasyouwouldbedoneby in the pre-Raphaelite style creates tensions with Kingsley’s themes purity and morals displayed through her literary description.

Victorian Fairy Art

Victorian fairy painting was partly inspired by the pre-Raphaelite emphasis on naturalism and detail, as well as the religious changes in society and art of the time (Bown 110). The Victorians were greatly fascinated with fairies. Not only was the fairy world a “relief from and consolation for the Victorians’ overwhelming consciousness of the modernity of their world” through the playful combination of detailed depictions of nature and a supernatural world, it was also a coping mechanism used to deal with the conflicts between religion and science Darwin’s theory of evolution created (Bown 45). As Nicola Bown explains, “Science has attempted to usurp the point-of-view of the deity, for it has adopted the perspective which sees and knows the world absolutely” (120). The implication that the Biblical account of creation could in fact be false made many question their faith and the teachings that had been passed down for hundreds of years. Fairies and their fantastical environment allowed the Victorians to escape their overwhelming and expanding world that shook up the social and cultural norms that they were born into.

Fig. 5. Joseph Noël Paton, Under the Sea I.

Paton, as a pre-Raphaelite and a religious man, produced many artworks containing fairies as subjects and was regarded as “one of the most pre-eminent fairy painters of his day” (Trimpe et al. 108). His Scottish heritage and familiarity with Celtic legends and folklore also influenced his eye for fantasy scenes (Story 21). As an example, his works Under the Sea I and II demonstrate Paton’s pre-Raphaelite emphasis on the detail and beauty of nature along with his ability to depict winged fairies and other fantasy creatures with the same amount of care (fig. 4, 5). The female subjects of these works are visually reminiscent of the pre-Raphaelite “erotic” woman, while the ocean scenery resemble the pre-Raphaelite emphasis on displaying nature accurately and beautifully. In addition, the fairies’ wings in these paintings are visual proof of Paton’s ability to mix the supernatural with the natural. The woman’s wings in Under the Sea II resemble fish fins as she floats under water and the wings on the woman in Under the Sea I seem like an insect’s as she flies over the waves, both of which take a natural element and turn them supernatural (fig. 4, 5). Paton was able to expertly combine the naturalism of the pre-Raphaelites with the supernaturalist escapism of the world of fairies by painting them “with the rarest spirit and fidelity, and all as it were instinct with life” (Story 107). His ability to combine the natural with fantasy, and make everything seem cohesive and real, is in part what elevated him and his works above other fairy artists of the time. These qualities made Paton an excellent candidate for creating illustrations to go along with the publication of various Victorian fairy tales, such as The Book of British Ballads and, of course, The Water-Babies (Trimpe et al. 55).

Paton’s work for The Water-Babies is very reminiscent of the Victorian fairy art style and his own works of the genre. For example, in the second plate illustration one of the girls wears a seashell hat, creating a feeling of playfulness that was often present in Paton’s fairy paintings (fig. 6). In fact, in another one of Paton’s fairy paintings, The Quarrel of Oberon and Titania,one fairy in the bottom left of the painting wears a seashell hat in the same way the girl in the illustration does (Paton).In addition, the fact that the setting of the novel and the illustrations are under water adds to the supernatural escapism that fairies brought to the Victorian world while also catering towards Kingsley’s interests in nature. The two illustrations are very similar to Paton’s Under the Sea I and II in setting, composition, and style, with a balance of natural beauty and diversity in a supernatural world (fig. 4, 5).

Paton’s illustrations of the water-babies, reminiscent of both the classical innocence of infancy and the playful nature of fairies, also seem to encourage the novel’s theme of growth along with faith. In the early stages of Tom’s life as a water-baby he acts like his usual mischievous self. For example, Tom teases the dragonfly for being ugly before his metamorphosis and tries to catch him after his transformation (51-2; ch. 3). Then, much later, the novel’s final chapter involves Tom’s journey to willingly help Grimes, his former caretaker and abuser (ch. 8). In one way, Tom’s journey leads him to become a kind of “redemptive child”, or, as Emily Learmont describes, one who “is able to offer spiritual rehabilitation to adults” (33). Because of the assumptive closeness of infants to God and heaven, the ability of young children to help adults reach a similar purity was a common reoccurring theme in Victorian literature and art (Learmont 33). The growth Tom exhibits from a mischievous and immoral child to a well-mannered child willing to help his abuser is visually displayed in the two artistic depictions of the water-babies in that they depict Tom being taught by a higher power and Tom being physically raised up with the help of other water-babies (fig. 3, 6). At the same time, the images can also be interpreted as a visual representation of Tom becoming a “redemptive child” symbol by the end of the novel. The fairy-like playful side of Tom becomes the clean and morally good Tom through his journey described in the novel, where he is then able to help an adult character to a level of redemption. This transformation can even be visually seen in the illustrations as well, as the second drawing depicts Tom as more life-like than the other water-babies in the image, almost as if a photo reference was used (fig. 6). Though maybe not purposeful, this could represent Tom’s metamorphosis from a childish fairy like in the first image into a well-rounded “man” (fig. 3).

Scientific Illustration

Like with the shift in Victorian artistic communities, both the definition of and approach towards science changed drastically in the nineteenth century. These changes were especially brought on by the publication of Charles Darwin’s Origin of the Species in 1859. Charles Kingsley himself was quite involved in the growing focus on the natural environment, its inhabitants, and their origins. As explained above, it was often encouraged for clergymen to familiarize themselves with nature and the natural sciences to help create stronger connections with God (Klaver 17). Kingsley was specifically interested in marine biology, and even “sallied out with his children to explore rock-pools and collected all the curiosities that had been washed ashore” and sent his findings to zoologist and biologist friends to dissect and study (Klaver 353).

Kingsley was also interested in studying his subjects himself as well, and often illustrated his own notes and gave lectures on his findings. His wife Frances Eliza Grenfell describes that, “In his night-schools, which were well attended, he gave lectures on mines, shells, and other subjects connected with Natural History, illustrated with large drawings of his own” (Kingsley 233). He would give sermons during the day, and then present his own research on sea-life in the form of illustrations and lectures in night-schools. In 1855 he went even further and published Glaucus, or, The Wonders of the Shore, a detailed book containing specifics about a wide variety of sea-life and their living environments and ecology based on Kingsley’s own observations and findings (Kingsley).

Glaucus also contained multiple intricate and comprehensive full color illustrations by George Brettingham Sowerby, a member of a family of very well-known natural history illustrators. These illustrations included both detailed individual specimen sketches and fully depicted scenes like the plate seen in figure 7. The full color aquatic scenes allowed for more aesthetically attractive visuals than the more common separate specimen sketches that were often present in strictly scientific works. Not only are they more efficient for displaying multiple different specimens at once, but the scenes also introduce the reader to the creature’s natural environment and are more exciting as a result.

Sowerby’s illustration work in Glaucus greatly resembles Paton’s naturalistic pre-Raphaelite background scenery in both his personal work and in The Water-Babies. For example, in Under the Sea II Paton depicts multiple species of fish, shells, snails, starfish, and vegetation in great detail, reminiscent of Sowerby’s under water scenes (fig. 4). Under the Sea I also shows a detailed seashore with crashing waves and more aquatic creatures (fig. 5). The background of Paton’s first Water-Babies illustration similarly contains detailed images of sea life like fish, snails, and starfish, along with a variety of aquatic plant life, which is also reminiscent of Kingsley’s fascination with marine biology (fig. 3). The second plate illustration displays similar detail and realism in both its figures and background: a hermit crab pokes out from the side of the image, sea anemones are scattered around the rocks, and little Tom seems to be seated on top of a jellyfish (fig. 4). Not only do these environments mirror Sowerby’s full color Glaucus illustrations in their accuracy and variety, but they also are reminiscent of Paton’s pre-Raphaelite and fairy painting details. The scientifically accurate illustrations add visuals to Kingsley’s wonderfully descriptive underwater world and context to the colorful lives of its characters like the lobster, the salmon, and the water-babies themselves.

Paton expertly uses his experience as a pre-Raphaelite and fairy artist to display the water-babies that Kingsley envisioned in his own way. His illustrations also display the novel’s themes of morality, cleanliness, and growth while providing some contradicting imagery related to the changing cultural values at the same time. Paton expresses Kingsley’s fascination with marine biology as well by incorporating detailed scenery and backgrounds reminiscent of scientific illustrations of the day for the water-babies and other creatures to live in. The Water-Babies is a wonderful and intriguing mixture of science and religion, fish and fairies, and new and old art movements. The combination of the novel with the beautiful illustrations helps to communicate the complex themes to its readers while also visually displaying the fantasy world Kingsley created, allowing the imagination of the reader to run wild.

Works Cited

Bown, Nicola. Fairies in Nineteenth-Century Art and Literature. Cambridge UP, 2001.

Emison, Patricia. “Raphael’s Dresden Cherubs.” Zeitschrift Für Kunstgeschichte, vol. 65, no. 2, 2002, pp. 242–50. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/4150686. Accessed 8 Apr. 2022.

Kingsley, Charles. The Water-Babies; a Fairy Tale for a Land-Baby. Illustrated by J. Noël Paton, New York, Macmillan, 1881.

Kingsley, Frances Eliza Grenfell. Charles Kingsley, His Letters and Memories of His Life. Oakland, Scribner, Armstrong, 1877.

Lavin, Marilyn Aronberg. “Giovannino Battista: A Study in Renaissance Religious Symbolism.” The Art Bulletin, vol. 37, no. 2, 1955, pp. 85–101. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3050701. Accessed 12 Feb. 2022.

Learmont, Emily. “Childhood Enshrined: The Lullaby (1862) by Joseph Noël Paton (1821-1901).” The British Art Journal, vol. 20, no. 1, 2019, pp. 30-37. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/48617284. Accessed 12 Feb. 2022.

Lessens, Ronald. “Henry Wallis (1830-1916), a Neglected Pre-Raphaelite.” The British Art Journal, vol. 15, no. 1, 2014, pp. 47–59. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43490700. Accessed 21 Apr. 2022.

Millais, J. E. Christ in the House of His Parents.1850. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christ_in_the_House_of_His_Parents.

Paton, Joseph Noël. Illustration 1. Circa 1881, The Water-Babies; a Fairy Tale for a Land-Baby by Charles Kingsley, New York, Macmillan, 1881, p. 2.

—. Illustration 2. Circa 1881, The Water-Babies; a Fairy Tale for a Land-Baby by Charles Kingsley, New York, Macmillan, 1881, p. 121.

—. The Quarrel of Oberon and Titania. Circa 1849, National Gallery of Scotland. Victorian Fairy Painting, by Pamela White Trimpe, et al., Royal Academy of Arts, 1997, p. 110.

—. Under the Sea I. CGFA, http://www.sai.msu.su/cjackson/p/p-paton5.htm.

—. Under the Sea II. CGFA, http://www.sai.msu.su/cjackson/p/p-paton6.htm.

Raphael. Sistine Madonna. 1512. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sistine_Madonna.

Sowerby, George Brettingham. Plate 11. Circa 1859. Glaucus, or, The Wonders of the Shore, by Charles Kingsley, London, Macmillan, 1859, p. 263.

Story, Alfred Thomas. Sir Noel Paton: His Life and Works. London, 1895.

Trimpe, Pamela White, et al. Victorian Fairy Painting. Royal Academy of Arts, 1997.

3 thoughts on “Illustrations to Charles Kingsley’s The Water-Babies: Inspiration and Influence”